How To Build A Roster In The Modern Portal Era

A study on the roster construction strategies that lead to success for high majors

For the first time in history, more than half of the points scored in Division 1 men’s college basketball will be scored by players recruited through the transfer portal, not from high school. The rule changes in the sport over the last several years have led to dramatic changes in how coaches recruit players. Each offseason has felt more hectic than the previous, with many coaches scrambling to decide on a fresh recruitment strategy every offseason.

Longtime Kentucky head coach John Calipari recently revealed that he is changing his “formula” for recruiting as he takes over at Arkansas.

Given that close to 2000 players entered their names in the portal from D1 schools this offseason alone, the changing climate has led to many discussions on the best way to build rosters in the modern portal era. While the portal gives every coach an opportunity to completely rebuild in a single summer, questions have been raised about whether transfer-reliant teams actually work:

To tackle these questions, I have conducted a study on the roster construction techniques used over the last several seasons to determine the best strategies for success. In this article, we will answer many of the recruiting questions that are being talked about in today’s game:

Can you have too many transfers?

Is transfer recruitment more critical now than high school recruitment?

How valuable are returning players?

Do you need freshman talent to be elite?

Do you need star players on your roster?

Should you prioritize returning players over transfers?

Is there a “formula” for roster composition?

For the purposes of today’s discussion, we will only talk about high-major teams, as the resources at mid-major schools dictate that they approach roster construction in a very different manner from high majors. I will dedicate a future article to talking about these concepts for mid-majors.

Roster Construction Best Practices

We will start with the main conclusions of the 3-year study and then explain each one more in-depth along with the accompanying research:

1. Fill your roster with good basketball players

2. Returning players should account for at least 50% of the playing time

3. Prioritize recruiting players who will play at least 2 seasons for you

Talent Matters

The most important (and obvious) strategy in roster construction will always be to fill your roster with skilled, talented players. It doesn’t take a statistical study to convince anyone of this point, so I won’t spend much time on the topic.

The strength of a team’s squad in the preseason will always be the strongest indicator of success during the season. As a part of this study, I calculated a preseason roster score for every team that takes the preseason BPR projection for every player on the roster and added them all up, weighting each player based on how many minutes they are likely to play. These minute predictions are based on how each player ranks relative to other teammates in their BPR projection. The best players on a team typically are predicted to play around 30 MPG, and the worst players in the rotation are expected to play around 10 MPG.

The graph below shows how every team’s preseason roster scores against their end-of-season team efficiency rating at EvanMiya.com over the past three seasons.

Unsurprisingly, there’s a high correlation between roster score and team performance during the season. Suppose a coaching staff is deciding between two players, one who is definitely a better player than the other. In that case, it’s always the best choice to go with the more talented player, no matter what avenue of recruiting that player comes from (returning player, transfer portal, or high school).

A Three-Year Study

With the obvious out of the way, let’s dig deeper into the roster construction of high-major teams over the last three seasons. I chose to limit the study to the 2021-22, 2022-23, and 2023-24 seasons because they most closely represent the current landscape of college basketball, with plenty of immediately eligible transfers and NIL playing a massive factor in recruitment.

The main variables that I took into consideration for this study were:

Preseason roster score ranking

The percentage of minutes played during the season by returning players

The percentage of minutes played by new transfers

The percentage of minutes played by freshmen

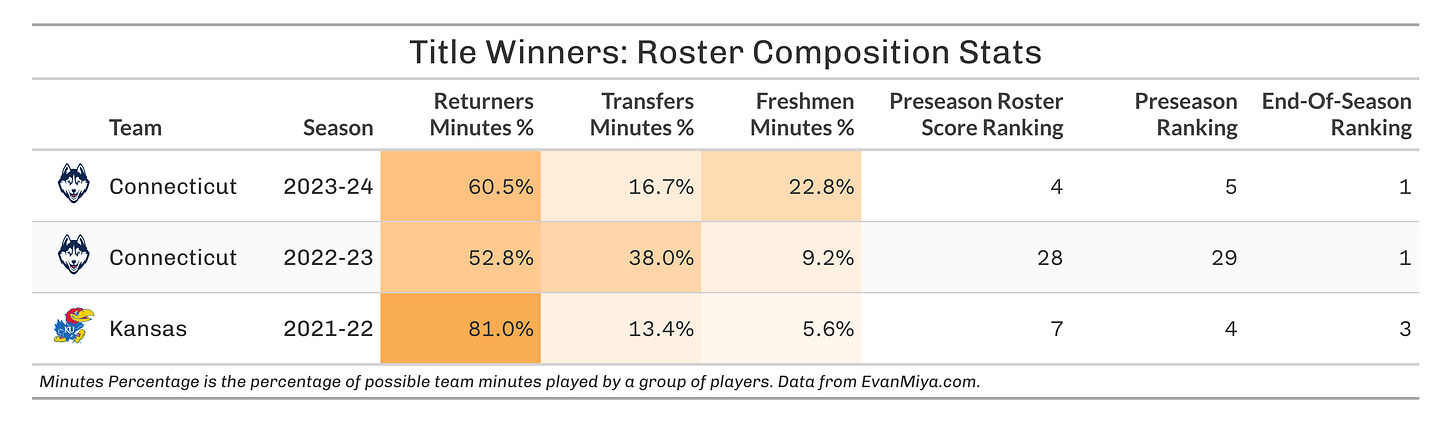

The following table shows how the previous three champions fared in each category. Notice that each title winner used returning players for over 50% of the available minutes.

Since it’s impossible to make sweeping conclusions on roster construction from just three teams, let’s expand our pool of “successful teams” to all of the 1 seeds from the past three seasons. Every team had a preseason roster rank inside the top 30, with 10/12 having top 15 rosters. Almost all of the 1 seeds leaned mostly on returning players, as only two teams had returning players play less than 50% of their team’s minutes (Alabama 22-23 and UNC 23-24).

Let’s expand our list of successful teams a bit further and compare all teams that finished in the top 10 at the end of the season (all of which made the tournament) to all high majors that missed the NCAA tournament entirely.

The differences are pretty stark. Top 10 teams, on average, had returners play about 60% of the available minutes during the season, while teams that missed the tournament were only at 51%. The reliance on transfers was way lower for top 10 teams, at just 23% of the minutes, compared to 35% for high majors that failed to get a tourney berth. Top 10 teams also took one less transfer in the offseason on average than teams that missed the tournament.

Hitting At Least 50% Minutes From Returning Players

If you compare two rosters who are of similar talent in the preseason, the team that is structured around returning players typically performs better than the team that is structured around mostly new transfers and freshmen.

To illustrate this, the graph below takes every D1 team in the last three seasons and places them into groups based on their preseason roster score ranking. For example, all teams ranked between 110th and 70th are in one group, while all teams ranked in the top 35 are in another group. When you look at the average end-of-season ranking at EvanMiya.com for teams within each group, the teams that gave returning players at least 50% of the team’s minutes during the season always finish better on average than the teams that gave a majority of their minutes to new players.

For example, among teams who had top 35 preseason roster scores, those that played returning players at least 50% of the time typically finished around 18th in the country at the end of the year. However, teams who played returners less than 50% of the time finished around 25th on average, 7 spots worse. This difference is seen for every grouping of teams, no matter what their preseason roster talent was.

Some other graphs in the footnotes1 further show that reliance on returning players is typically at odds with giving more minutes to transfers. More often than not, teams who build rosters mostly around returners fare better, while teams who are mostly comprised of transfers do worse.

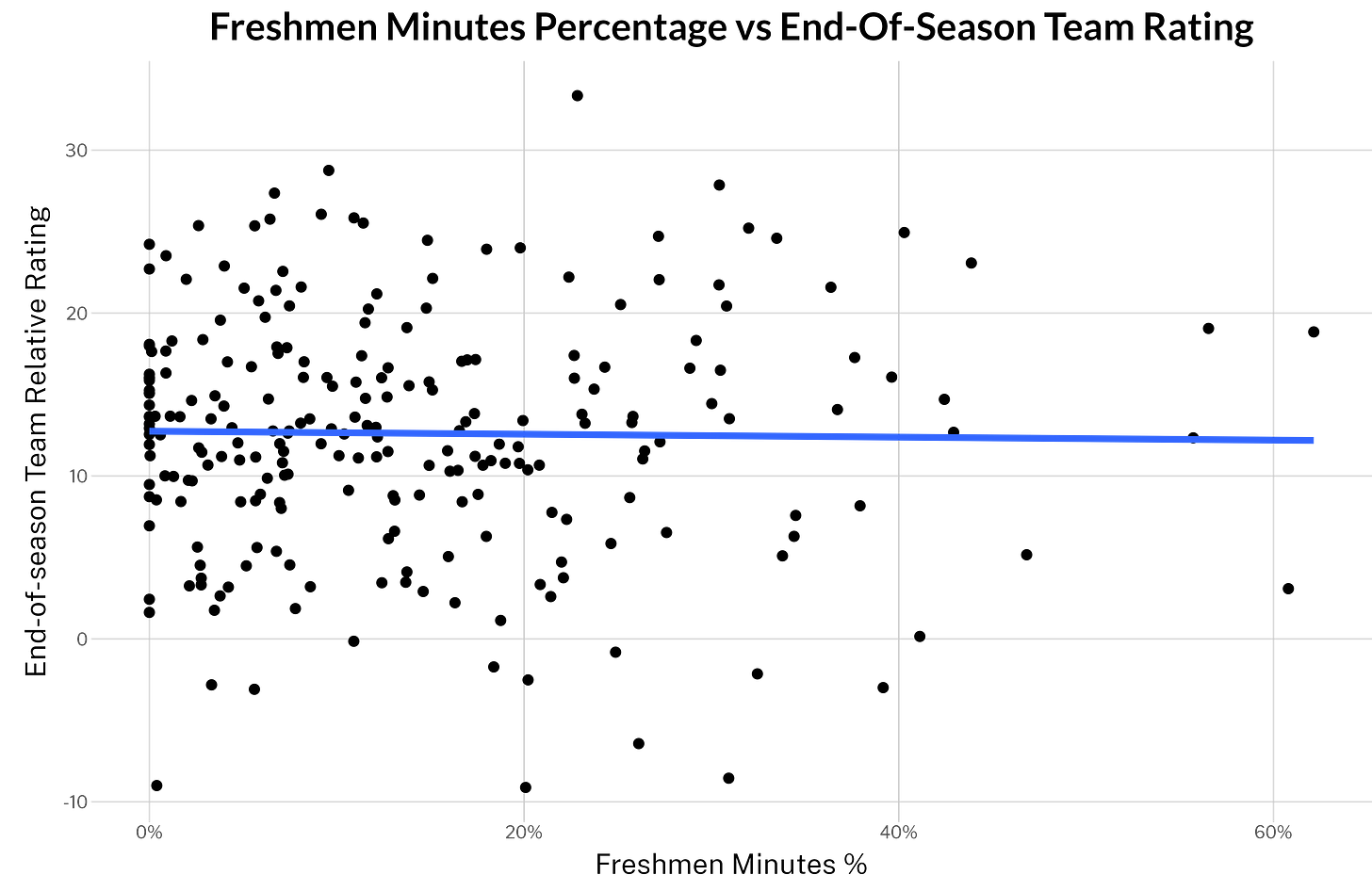

Interestingly, the percentage of minutes played by freshmen doesn’t seem to impact whether a team performs well or not. In my opinion, teams built around transfers struggle more often because transfers often fill a void for a potential returning player who was not retained. Teams with many transfers will likely have very few returning players, and vice versa.2

The same is not the case for rosters studded with freshmen. These teams are more likely to still have a good number of returning players, unlike teams filled with transfers.3

Broad Conclusions

Based on the results of this study, the most crucial factor to team success, beyond prioritizing good players, is trying to maximize the role returning players will play. Having returners take up at least 50% of the minutes played is a safe benchmark, but teams with an even higher percentage are likelier to play well.

Having talented freshmen and transfers on the roster is not bad, but recruiting these players should not come at the expense of losing similarly valuable players already on the roster.

A secondary takeaway is this: Teams that prioritize recruiting (or retaining) players who will play for them for multiple years will reap the benefits down the road. The true value of a freshman or transfer can often come in the 2nd or 3rd year that he plays for the same team. Given how much more success teams with returning players have, it is wiser to recruit a player who is more likely to play multiple years at your school than a similarly skilled player who will just play one season and graduate or transfer away.

Case Studies

One of the most interesting parts of this research is analyzing teams that take some of these roster-building strategies to the extreme. Here, we will examine outlier teams from several categories and provide insight into whether these approaches to roster construction work.

Running It Back: Teams Who Return Maximum Players

The table below shows the high majors from the last three seasons with the highest percentage of minutes played by returning players. All of these teams had returners make up at least 89% of the possible minutes on the court:

Nine of the ten teams made the tournament, 8/10 were rewarded with an 8 seed or better, 6/10 finished in the Top 25 at EvanMiya.com, and one made the Final Four (Villanova 21-22). Teams that “run it back” typically have high, safe floors. They don’t usually underperform and are likely to have pretty good seasons, if not better.

Start From Scratch: Teams Who Return Minimum Players

The table below shows the high majors from the last three seasons with the lowest percentage of minutes played by returning players. Every team had returning players play less than 16% of their team’s minutes:

The results are pretty disappointing for this group. Only one team out of ten made the tournament (Iowa State 21-22), although St. John’s in 23-24 probably deserved to make the dance as well. Half of the group finished outside the Top 100 at EvanMiya.com.

The most hyped teams from this group in the preseason failed spectacularly. LSU in 2022-23 was loaded with transfers but dropped almost 100 spots from the beginning of the season to the end. Only 2.5% of their minutes were played by returning players. Memphis in 2023-24 also had an exciting transfer class, but after being ranked inside the top 10 in the AP poll after a promising start to the season, they flopped and missed the tournament (9% returner minutes)

Young And Talented(?): Teams Who Maximize Freshmen Minutes

To analyze teams that rely heavily on freshmen, I will break them into two categories.

First, we will look at the teams with top 20 preseason roster scores with the highest percentage of minutes played by freshmen. These teams typically had elite five-star freshmen and were likely to make the tournament. Every school on this list had freshmen account for 30% of the minutes or more, with Duke 22-23 and Kentucky 23-24 over 50%.

These teams with highly touted freshmen classes have fared pretty well, with all ten teams making the tournament. What’s interesting, though, is that while the freshman talent was sky-high, these teams also had the returning players to pair with freshmen to make it work. Among this group, 43% of the minutes played were by returning players and 41% by freshmen. Generally, it’s hard for teams with big-time high school prospects to fail, especially if there are equally skilled returning players to match with them.

How does this apply to Duke’s incoming freshmen class for the 2024-25 season? Based on my roster projections, an estimated 44% of Duke’s minutes will be played by freshmen, 34% by new transfers, and 22% by returning players. That’s a pretty low amount of playing time for returners, but given that Duke will likely have a top-10 roster in the preseason, talent will probably win out.

Next, we will take schools ranked outside the top 20 in preseason roster scores and look at the 10 teams with the highest burden on freshmen from that group. Every team in this category played freshmen for at least 34% of the team’s minutes:

The results aren't pretty for teams who rely heavily on freshmen but aren’t among the nation’s elite rosters. Just 20% of this group made the tournament, and 6/10 teams finished the year outside the top 90 in the country. While the average percentage of freshmen minutes from this group was 43%, just 33% of the possible minutes were played by returning players. The most glaring failure is UCLA from 2023-24, which had six incoming freshmen and a top 40 roster but finished 92nd at EvanMiya.com.

The Importance of Star Players

Another interesting takeaway from my research is the presence of star players on many of the most successful teams. If we look at every team that finished in the Top 10 at the end of the year, every single team had a player ranked inside the top 100 players in the preseason at EvanMiya.com, and 28 out of the 30 had at least one top 50 player.

What About Mid Majors?

Stay tuned for a future blog article on optimizing roster construction for teams outside of the high-major ranks later this offseason.

Scatterplots showing the correlation between returning player minutes %, transfer minutes %, freshmen minutes %, and end-of-season rating:

The graph below shows each high major team’s percentage of minutes played by returning players compared to their end-of-season team rating at EvanMiya.com. There is a clear positive trend between teams that rely more heavily on returning players and better team success.

By contrast, the scatterplot below shows the negative correlation between the percentage of minutes played by transfers and team rating:

Interestingly, the reliance on freshmen doesn’t seem to impact whether a team performs well or not, as seen in the graph below.

Your work is always awesome, thanks Evan.

Question about causality - it seems possible to me that teams have a lot of transfers because they are bad, not that they are bad because they have a lot of transfers.

For example - a team that has struggled over the last few seasons fires a coach, lots of players leave, new coach comes in with a new system and has to recruit basically from scratch, leading to a bad next season. They weren't bad BECAUSE of the transfers, it was just another symptom of their poor play.

Very interesting. Thanks, Evan.